Carbon labelling policies

Carbon Labelling is supported in the framework of the Intelligent Energy Europe programme

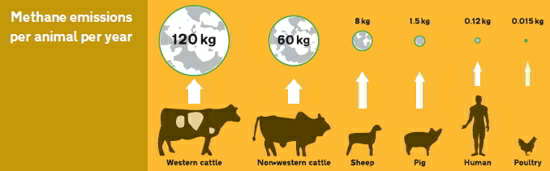

It has been shown that the carbon footprint of food products (‘foodprint’) can vary substantially. Depending on its production method (organic versus chemical), its content (meat versus vegetarian or vegan), transport routes (air freight, sea freight or local), processing method (fresh versus deep-frozen) and disposal of residues (use as organic fertilizer versus waste), each food item is responsible for a certain amount of GHG emissions during its life-cycle.

Making this information available to the consumer increases transparency in the food market, raises awareness of the consumer, creates incentives for the industry to lower its carbon footprint, and rewards climate friendly products. Consumers should know whether the organic kiwi from New Zealand or the home grown chemically fertilized apple does more harm to the climate. In general, environmental labelling has been a success story since the 1980s. Labels, such as the Energy Star, energy efficiency ratings or the Nordic Swan label have changed the behaviour of consumers and manufacturers. An Eurobarometer survey showed that for an overwhelming majority of Europeans (83 percent) the impact of a product on the environment plays an important aspect in their purchasing decisions.

An evaluation of the specific circumstances of the political and regulatory environment will determine the best choice in each case. Whereas a mandatory label ensures a broad participation, voluntary schemes might have a better acceptance in the industry. A food label should be based on total lifecycle emissions, as opposed to considering only the use-phase. Possible are both, comparative labels which provide consumers with product information through use of a specific number (e. g. ‘1 kg CO2’) or rating (e. g. A–F or 1–5 stars), or endorsement labels which prove that the product meets certain criteria (e. g. below average carbon footprint).

Implementing new labelling schemes necessitates conformity assessment procedures involving testing, inspection, certification, accreditation and metrology. These processes are essential for the effective implementation and acceptance of the scheme.

The EU Commission has taken a first look at this issue but, not surprisingly, has received opposition from the food industry. However, the example of the UK Carbon Label and the Swedish climate labelling initiative show that the concept can be implemented and, with the assistance of governments and industry, can be established on a larger scale.

Case study: Sweden’s Klimatmärkning

In Sweden, the two major certification bodies, KRAV and Swedish Seal, have developed a climate label for food. As the project has been joined by several major food and agriculture companies, the Swedish climate labelling initiative has become the first comprehensive and country wide policy of its kind in Europe.

The climate label covers the food chain from farming to the sale of the produce. So far, criteria for meat, fish, milk, greenhouse vegetables and agricultural crops have been set. Food produced and distributed with at least 25 percent less GHG than comparable products can be labelled with a respective note. In this way the label focuses on the climate friendliest products within a group, but does not help the consumer to choose between meat and beans.

The climate label is accompanied by an information and education campaign, which resulted in recommendations for climate compatible nourishment. In addition, the initiative works with the industry to implement measures to reduce the GHG emissions of food production.

According to press reports (Spiegel-online of 7th Nov. 2009) the climate label increased the sale of Max burgers by 20 percent. Experts are cited to expect a 50 percent reduction of GHG emissions in the Swedish food industry, if the population would switch to climate friendly alimentation. The labelling initiative maintains that 60 percent of consumers would like to see a climate label on products.

Anna Richert, climate expert of the label initiative, says: “The strength of the label is that reductions in climate impact have been made wherever possible. The producer participates in making the food chain more sustainable.”

Click here to access Klimatmärkning homepage.